Guest Blogger: James Johnston

Any time you can be in the woods hiking around and calling it work it’s fun, but reconstructing historical fire in old-growth Douglas-fir forests is…. less fun than in other areas. For starters, the slopes tend to be really steep and the trees are really big and hauling around gas and giant wood samples gets old.

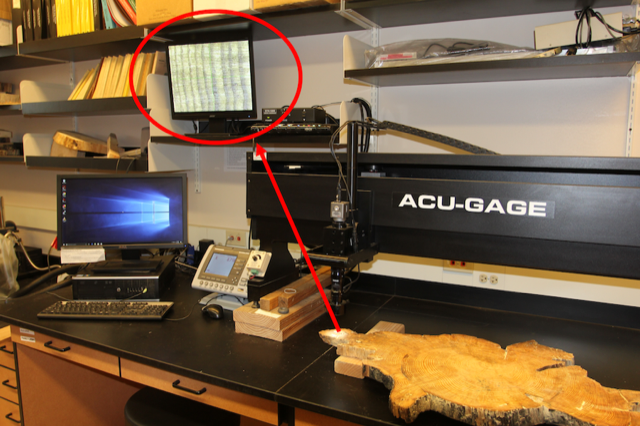

Finding fire scarred trees in stands with oak and ponderosa pine is relatively easy. Ponderosa pine typically has a cat face like this one which allows you to easily see evidence of historical fire. You saw out a partial cross section and use the unique pattern of wide and narrow rings to cross date that sample, and assign to each of those fire scars a calendar year.

In old-growth Douglas-fir/western hemlock forests you can rarely see visual evidence of historical fire and so I’ve been using a chainsaw to basically excavate these large stumps left over from logging operations.

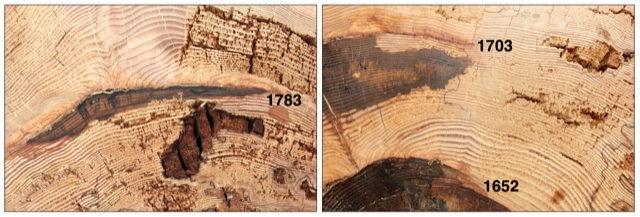

If you crack open enough of these stumps, you can find fire scars buried in these giant chunks of wood. They look like this:

Most scientists assume that these old-growth Douglas-fir/western hemlock forests go hundreds of years without fire, and when they do burn, it’s generally stand replacing fire. But when we crack open these big stumps, we are seeing far more evidence of historical fire than predicted by theory.